Sigma

Sigma Sigma

Sigma

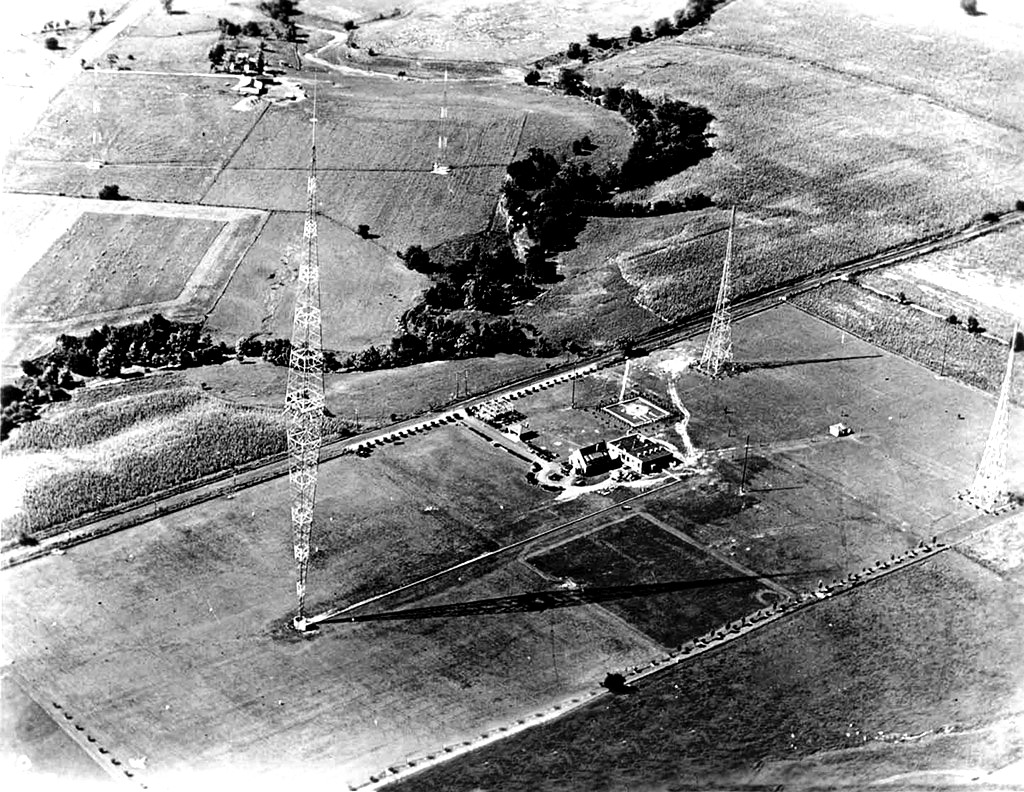

I was working at KCRA Sacramento. The station had a microwave intercity relay link between Sacramento and Stockton. It connected their Stockton news bureau with the Sacramento studios. Actually, the link consisted of two microwave links. One from Stockton to the transmitter site, at a place called Walnut Grove. All the Sacramento stations had their transmitters and towers there. These sites are referred to as an 'antenna farm.'

At Walnut Grove the Stockton receiver hands the signal off to the second microwave transmitter, for the rest of the trip to Sacramento. There was a problem with that second microwave transmitter. I was asked to go out to the transmit site and have a look at the microwave receiver and transmitter. I hadn't been with the station too long and was unfamiliar with the site. Silly me, I assumed the two devices were on solid ground in the transmitter building. WRONG!

Right before we left the station for a the 20‐mile drive to the site I found out that the receiver/transmitter pair was at the top of the tower, 1500 feet above the transmitter building.

The one thing I never did was climb. I did climb a hundred‐foot tower once. But it had a full cable climb system as part of the tower, including full safety harness.. Sort of a rachett system where to desend you had to physically lean away from the ladder to disengage the safety rachet track. Totally fall proof but still disconserting. 1500 foot climb. Not me!

No problem, they said. The tower had an elevator.

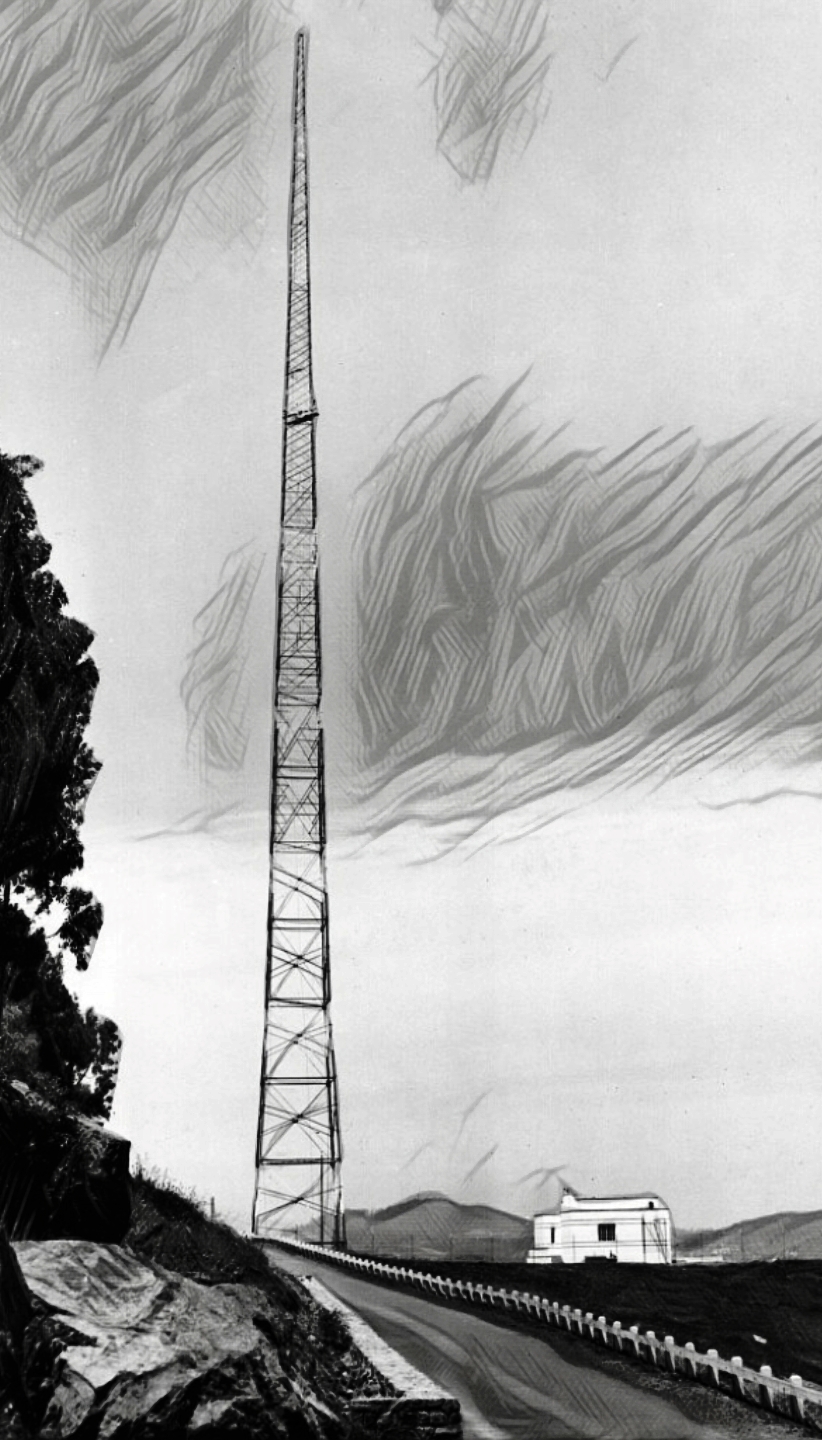

It is what is called a Candelabra tower. That's because at the top it looks like a candle holder that can hold three candles. The top is triangle‐shaped. Instead of holding three candles. Each point held an antenna. The three original stations in the market each had an antenna up there.

Unlike AM radio, where the entire tower serves as the antenna, FM, TV, and most other forms of RF use the tower merely as a platform to elevate the antenna. There is an old axiom in RF circles: given a choice between transmit power and height, always take height.

AM is at a low frequency, centered around 1 megahertz. TV starts at frequencies 50 times greater than that and goes up a few hundred times higher than where you find AM on the dial. While you can walk up to the base of a FM and TV tower and touch it. Do that with an AM tower, since it is the actual antenna, you're going to have a bad day. Besides the electric shock, you’re probably going to get a nasty burn.

That is why AM towers have fences around them. Most towers have fences to keep the knuckleheads from trying to climb them. Although AM was invented first, FM not until the 30s, and TV was introduced in the 40s, AM was, and still is, as much black magic as science to many.

Because the frequency is so low with AM, the antenna pumps as much of the signal into the ground as it does into the air. So that axiom about height doesn't hold for AM. AM transmitters and their antennas are generally placed in low areas with good ground conductivity. Such as in marshes or near bodies of water.

There is a notable example of bad AM tower placement, 40 air miles southwest of this tower in San Francisco. In the late 30s, KYA decided to move its AM transmit site to a hill at the southeast edge of San Francisco. This AM transmitted on 1260MHz. It was a rocky hilltop with bad ground conductivity.

The high elevation of the antenna, along with a poor groundwave component, resulted in unpredictable signal reflections, leading to spotty reception in parts of San Francisco.

The high elevation of the antenna, along with a poor groundwave component, resulted in unpredictable signal reflections, leading to spotty reception in parts of San Francisco.

When Candlestick Stadium was built in 1960, just to the east of the hill KYA was on, its PA systems, and even broadcast equipment brought into the stadium was plaqued by KYA's top‐forty programming. While over time the stadium interference issues were migated, eventually the station gave up on the location. Today the original AM tower is gone; there is now a tower with cell and a FM antenna in its place.

While on the topic of how counter‐intuitive AM can be has to do with the number of towers a single AM station might use. Most powerful AM stations are class A's, according to the FCC. Many in the industry call them blow-torches. They usually have just one tower. AMs with additional towers have those towers phased, not to get technical, let's say driven or powered in such a way that they limit the signal sent out in certain directions. They are called directionals.

Often only a single antenna is used during the day, with the additional towers used at night.

Often only a single antenna is used during the day, with the additional towers used at night.

Why? More AM voodoo. During the day, the Sun ionizes the layer of our atmosphere called the ionosphere. That allows AM signals to radiate out into space. At night, that layer is no longer ionized, and so it bounces those low‐frequency signals back to Earth, often hundreds, even thousands of miles away from the station. That is why at night you can often hear WLS out of Chicago, or WSB in Atlanta in many places in the country. I’ve heard KNBR, located on a marsh adjacent to the San Francisco Bay, all the way to Wyoming. That phenomenon is called skip, like skipping a stone across the water.

Getting back to my foray to the top of the world. It turns out we would be above the clouds. The central valley of California stretches about 400 miles. It runs from just north of Redding to 25 miles south of Bakersfield. This area divides into two regions: the San Joaquin Valley and the Sacramento Valley. The Sacramento area is drained by the Sacramento River. The San Joaquin area is drained by the river of the same name. A large inverse delta of many sloughs and tributaries separate the two. Since the Sacramento River runs right by KCRA's site it puts the site in the Sacramento Valley. KCRA built a 2000-foot tower north of this site in the 80s. The candelabra tower we visited that day became the backup. Although during the Analog to Digital transmission conversion, the Digital transmitter was at this old site until the conversion was complete and analog was history.

When we arrived at the site, it was foggy. What is known as tule fog shrouded the site. Tule fog is a thick fog that forms close to the ground in California's Central Valley. It gets its name from the tule reeds that used to grow in the southern part of the valley. Origninally, a good part of the Central Valley was swampy, and at many places hard to cross. The final stretch of the transcontinental railroad from Sacramento to the Bay Area didn't go straight to the bay at first. It made a detour of nearly 50 miles to the south to go around the entire delta region. South of Fresno, up until the middle of the last century, the largest lake in California was Lake Tulare. It was about 40 miles long and 20 miles wide. Huge investments in agriculture in the fertile valley soil captured and managed the water flow there. The lake was completely drained over time. But to this day, if we removed man and allowed nature to take back the land, the lake would form again.

So to get back on track, the term "tule fog" came from the tules that surrounded the lake. It forms on cold mornings, especially in areas with abundant water. This site had both ingredients that morning.

We get to the base of the tower and yes, there is an "elevator." It was a small two‐person elevator; it was called the "coffin." This elevator traveled up the center of the tower. A ladder that also ran the length of the tower paralleled this elevator, about 18 inches away.

Interesting fact: it took 20 minutes to travel up to the top, but only 18 minutes coming down. At about the 600-foot mark, we came out of the fog into a brilliant sunlit morning. We could see the coastal mountain range, which was visible about 40 miles to the west.

The person who was guiding us towards the top was an old‐time transmitter guy, who enjoyed his time on the tower. The problem was I found no enjoyment in this ride. I give him credit. He tried to lighten the mood by pointing out landmarks. Some were far away, while others were things we passed on the tower. Many towers have lots of appurtenances hung or mounted on the sides of the tower. Appurtenance is a fancy term for something of lesser value mounted on a larger thing. So as we accended, we passed various dishes and a myriad of various shaped antennas.

At about 1,300 feet, the struts supporting the triangular structure angled away from the central tower. I let out almost a gasp. Seeing those arms stretch out from the main tower as we got closer caused a sense of disorientation. At that, my guide asked me if I'd ever been up the tower before. All I could muster was soft no. He seemed a bit take back.

Finally reached the top. At the top of the tower, the elevator rises into the first story of a two‐story 'pillbox' type structure. The elevator's scissor gate is opened, and you must step out onto the ladder that we followed up and then over to the right to step onto the room's solid floor. A grated hatch keeps you from falling down the tower. Still, the grates give you a clear view of the tower shaft, which extends 1,500 feet below.

You couldn't see the tower base. The shaft seemed to collapse into nothing. Also, the Tule fog swirled through the bottom third of the tower. The issue was that the equipment I needed was on the second story. So, I had to climb that tower ladder up another twelve feet. I forgot to mention that to be productive we had brought a few tools and a couple of pieces of test equipment. We stowed some of that on top of the elevator cage, which they had to maneuver up to the second level. In this upper space, there were three equipment racks. I thought about the effort required to get them up over a quarter mile to reside atop a radio tower.

I made it up to the second floor, OK. I remember I never looked down. Then things started to go south. My guide said the chief engineer at the station asked him to check a dish on one side of the triangle. This triangle candelabra had three catwalks. They stretched out from the central pillbox. The struts I mentioned earlier came up to meet the ends of the three catwalks. There was also a lattice of other support beams that comprised this top structure.

Usually, as in many other industries, in any situation where a person could get in real trouble if they were alone, people worked as pairs. One looking out for the other. My tower guide definitely qualified; I don't think I was.

We decided to check on the dish first. I volunteered to go out to the dish with him. Big mistake.

To do that, we headed out towards one of the antennas, as each point of the triangle had an antenna on it. This tower used to be known as the "tall tower," but not anymore. Most of the other stations have teamed up on other, even taller towers. Now there are three 2,000-foot towers in the "farm."

I remember asking about using a safety harness and lanyards with rebar hooks. As you climb, you can use one hook to attach to something above while keeping the other securely connected below. You can then disconnect the bottom one, climb a few steps, and start the process over. My guide replied that it was only a catwalk.

So, we started out on one of the catwalks leading out from the pillbox headed toward one of the antennas. And by antennas I don't mean like one that used to sit on your house. Who has roof‐mounted antennas anymore? These are massive steel and copper pylons that often weigh thirty thousand pounds or more.

So, we started out slowly. I was concentrating on gripping those handrails. One hand clinched down on one side, then moving the other hand and again tightly gripping the other side. Getting closer to one of the antennas. Back then, OSHA hadn't realized that TV and other RF sources were a big target. At the time we never wore RF dosemeters. RF dosimeters measure the heat produced when RF hits the body. This is different from nuclear dosimeters, which measure gamma rays. I don't think many stations owned any. OSHA eventually required radiation risk signs at transmit sites. Later, they ruled that having these signs meant all your staff must be trained about the dangers. Nice cottage industry of training companies sprang up.

At one moment, I glanced back at the pillbox. It felt like I was floating in the air, away from the tower, watching it. Up to then I hadn't looked down, just straight ahead. I now looked down and through the grated catwalk floor saw 1500 feet to the ground below. The only clear thought I had was that the fog was burning off. In some places, I could see all the way to the ground. It is a blank after that. The next thing I can remember is my guide coaching me as I shuffled back into the pillbox. At that point, I don't remember what transpired, but somehow the microwave was working when we started the elevator ride down.

Never went up the tower again. Fortunately, many others saw it as a fun break from routine. They eagerly jumped at the chance to ride to the top. I remember during my time at KCRA when a group of parachutists somehow managed to get to the top of the tower and base jump off of it. Don't know if somehow they knew how to get access to the elevator or climbed the ladder to get to the top. Since at least four TV and one or more FMs where on the tower, it was suspected that they had inside help from one of the stations. It did turn out that one of the jumpers had connection to one of KCRA's news editors. But no one beleived she would have been able to facilitate any access.

Years later, one of the 2000‐foot towers was involved in a base jump attempt. The intruder's parachute got tangled in a guy line. Many resources from local and state agencies, along with one brave firefighter, were necessary to bring the jumper down safely. While many like the thrill of being so high up in a tower held upright mainly by guy wires, for me, it was one and done!